Tied to outmoded and unrepresentative developmental models, communities across Africa often fail to achieve their full potential. Drawing from the traditions and cultures that reflect the needs of local communities, AIKS can be a viable alternative model for community development and environmental regeneration.

Like all the other continents, Africa is endowed with virtually unlimited natural resources across its vast rich fertile environment. The continent has many lakes, dams, deltas, swamps and rivers, and 60% of its surface area is virgin land; within this, a plethora of natural resources can be found, including diamonds, gold, copper and platinum. This surely can form the basis for future economic growth. Combined with the African Indigenous Knowledge systems (AIKS), the African environment can become a sustainable tool for meteoric economic development, if a viable model is used. Because the main objective of AIKS is to use natural resources for community development in a sustainable fashion, they are sensitive to ecological realities. Furthermore, AIKS are directed towards the preservation and conservation of the environment. AIKS are particularly appropriate for preserving the ecological balance in the communities where they are used, because they have few or no side effects, on both the environment and human beings, because they are purely natural. The United Nations has acknowledged the value of indigenous knowledge systems, and has emphasised that they need to be preserved and used in research and policy. This give Africa a footing for using the environment for economic development, by embracing a system that has been a part of the continent for centuries.

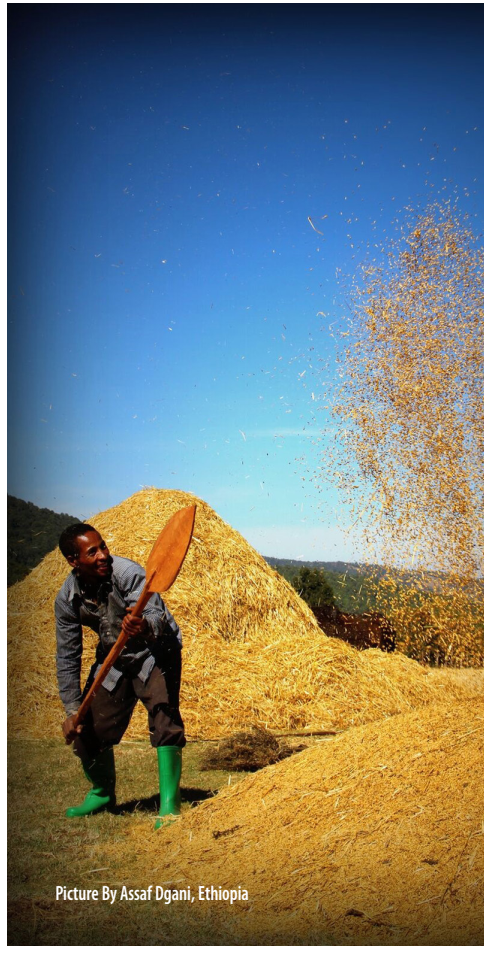

AIKS are part of Africa’s heritage, dating back to the pre-colonial era when they were developed in order to address various survival challenges. They are home-grown, and they have survived the test of time. However, the European settlers who colonized the continent in the late 19th century sought to destroy, denigrate, or marginalize them, replacing them with western views and approaches aligned with imperialism. The adoption and continuous use of AIKS indicates an academic, psychological and ideological shift to a neglected yet effective way of life that can be used sustainably for community development. The realisation of the resource that AIKS offers is both relevant and necessary for environmentally and ecologically sensitive activity. AIKS have been used as the engine for rural development, and have further been adopted for use in agriculture, forestry, soil preservation, fishery, and the pharmaceutical industry.

AIKS are geared to preserving and protecting the natural environment, wildlife resources and biological diversity, and embrace virtually all aspects of life including ecology. Africans were, and still are, conscious of the devastating consequences of the unsustainable utilization of natural resources. Nevertheless, AIKS survived colonisation, and remain the best way to sustainable tap into the continent's environmental resources.

Bound to modern economic models rooted in the philosophy of colonisation and its negative presuppositions concerning gender, race, discrimination and segregation, the continent failed to find the right path to development in the post-colonisation period. Thus, whatever economic model African governments chooses to adopt in the future, it should tap into AIKS, which have stood the test of time; and this should feed into an indigenous model of development which aspires to override a mentality set by the slave trade and colonisation. The strong, continually expanding informal sector in Africa is evidence enough that AIKS has the capacity to lead to development, given how resilient the system has been over time.

The use of AIKS is the only way forward in preserving Africa's vast environmental resources, which have been impacted by deforestation, the slaughter of wildlife, desertification in the Sahel, and the varied effects of climate change. If governments and civil society organisations can invest in the preservation of AIKS and make use of its practices, then Africa will not lose the soil, animals, and the environmental resources needed to sustain human life on an ongoing basis.

The power of AIKS has been demonstrated in many ways: examples include the discovery of the healing power of the African willow, the Hoodia plant and Iboga, in South Africa, Namibia, and Gabon respectively. These plants are changing the world of cancer treatment and anti-addiction therapy. AIKS are evident at all levels of community practises from material culture and the natural environment, religion, business etc.

This model has since proven how powerful it can be for development. One example is the maintenance of biological diversity, biological and crop pest control, water and soil conservation in Machakos, Kenya. A bio-pesticide project in Niger, funded by USAID, has been a tremendous success for local farmers. The Nyabisindu soil regeneration project in Rwanda, designed to reduce soil erosion and deforestation, also serves as a reminder of the need to look into models of development lying right in front of us. AIKS have also shown that they can provide a solution to climate change and the reduction in precipitation in the Sahel, through water harvesting projects that have supported local farmers. The Mossi farmers of Burkina Faso harvest water by constructing rock bunds and terraces to collect water, similar to the Zay system used by the Yatenga of Northern Burkina Faso. The Dagon of Mali and the Hausa of Niger have improved their farming practices by using sticks and grain stalks to redirect water to their fields. Lives have been changed by the use of these AIKS; more can be done to tap into its vast and untouched potential for human and economic development.

It must be pointed out that this model utilizes natural resources in quite systematic ways, and with deep respect for a “rich tradition” of norms and assorted practices, grounded in thereligio-cultural milieu. In the African context, the use, management and conservation of natural resources are shaped by spiritual and cultural practices and knowledge accumulated over centuries. As Riddell has observed, nature and culture have a symbiotic relationship with traditional religious practices in most African societies. It is these traditional religious practices that form the core of a particular culture. Thus, the utilization of natural resources does more than merely satisfy immediate needs; it is also a part of the conservation and celebration of human life. All these practices are attempts to protect and preserve natural resources, including land, forests and animals. One does not require enhanced vision to recognise that AIKSs were, and continues to be, an intellectual development model that also champions sustainability.

The practicality of AIKS is not at all remote, because they are already a part of everyday lives for many communities, such as Machakos in Kenya. The model seeks to preserve animal and plant species by engaging in more tree planting and vegetation regeneration, providing enough food for the local population and increased animal population. The local community, civil organisations and the government collaborated to implement this model; the result is one of the best AIKS models in Africa. Thus, there are so many opportunities for civil organisations, and even governments, to support development by using similar models. However, AIKS does presents its own challenges, especially with implementation. One is of choice, in a pool of so many indigenous systems; another is how to institutionalise such a structure, a challenge for Kenya, Niger and Mali, where AIKS models have produced enormous results.

Peter Uledi