A brief look at the education in refugee settings reveals challenges faced by peace education. This article presents these challenges and suggests shifting the attention towards quality education.

According to a report published by the United Nations Children’s Fund in 2009, “Education was once considered part of long-term development and peace dividend, rather than an essential part of humanitarian aid”. However, education became vital to the process of supporting the movement from relief to development. While fulfilling a human right, education also includes key messages for survival in challenging environments or in supporting peace building. This might include health and hygiene messages, as well as issues such as land mine awareness, conflict mitigation and reconciliation. The provision of basic education and informal learning opportunities face both challenge and opportunity in impacting the lives of refugee children and youth for good. However, appreciation for content, context and hidden aspects of curriculum, highlight the important role of teachers and the value of quality education.

Curriculum Content and Delivery

According to UNICEF’s 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, the aim of education is “The preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of indigenous origin.” Despite clarity on the intended outcomes of education — peaceful and tolerant citizens - there is no official definition of peace education. However, this popular term is used for a range of different educational activities and programs delivered by INGOs and funding bodies. This leads to the unfortunate assumption that peace education predominantly has priority above and beyond basic education rather than being an essential aspect of it.

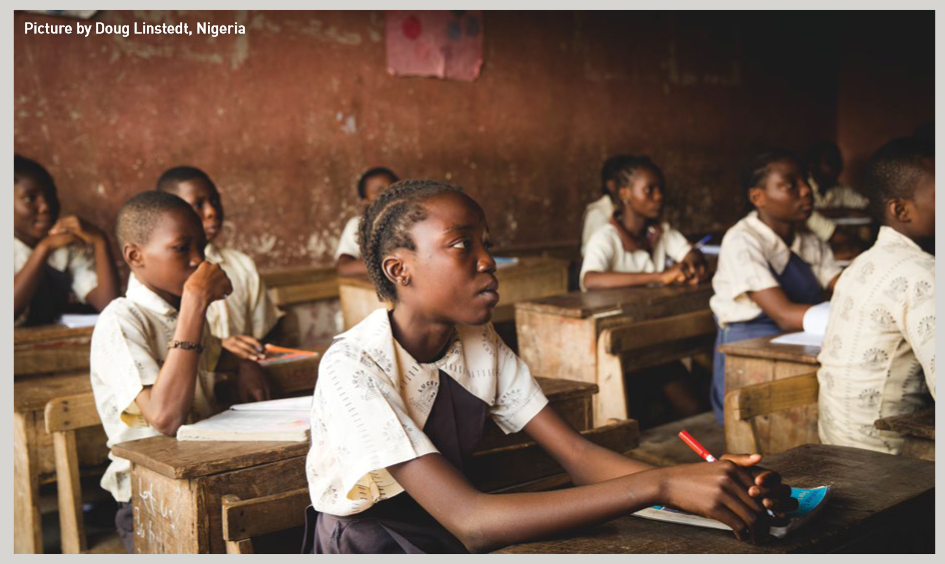

UNICEF, one of the leading agencies in the area of education, defines peace education as ”the process of promoting the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values needed to bring about behavior changes that will enable children, youth and adults to prevent conflict and violence, both overt and structural; to resolve conflict peacefully; and to create the conditions conducive to peace, whether at an intrapersonal, interpersonal, intergroup, national or international level.” On the practical level, these skills are challenging to facilitate in a refugee camp classroom. In this environment, teachers are born out of necessity and not choice, often feeling anxious and overwhelmed by entry into the profession. They too often have little or no pedagogical training to manage a child-centered, skill-focused curriculum. In addition, it is often difficult to find time to focus on peacebuilding messages in the classroom. Classroom time is highly focused on exam success and often pressured by teachers working in shifts, a system that is often needed for answering the constraints of providing education to refugee children.

The issue of untrained or poorly qualified teachers is not unique to refugee settings. Teachers who are equipped and supported, and who understand these challenging contexts, are more likely to use classroom practices that support inclusive and interactive student engagement instead of exams. This, in turn, supports child rights and the desired aims of education but still is very limited. Could professional development with teachers be as effective as a ‘peace education’ program, and also improve the overall quality of education?

Curriculum Context

The very idea of combining the discourse of human rights and peace education must also be considered (Notable critics include An-Na’im, 1998; Boyden and Ryder, 1996). In this consideration, these values should be questioned if they empower the students and answer the goals of education or only promote a western idea, which may undermine collective rights and action. As armed conflict that produces refugees is a collective action, focusing on individual or interpersonal behaviors can weaken this dimension. Such worries relate to the cultural impact of teachers in the classroom, and question the ultimate goal of peace education. When peace education focuses on the individual level, the foundations upon which it is built do not correlate with the context in which it is delivered. Thus, it is suggested that there is a need for community engagement with schools. School-based activities should become a component of community-based programming that involves the students’ parents and guardians in the educational process.

In his article published in 2004, Gavriel Salomon calls for the need for “peace education” programs to be aligned with the context in which they are intended. He highlights the diversity of settings, conflicts and community needs, which require inclusion and adaptations for the setting, and are often at odds with centrally prepared educational materials and training. Further discussion of education in refugee settings broadens our understanding of the challenges facing curriculum and context. Should education mirror that of the home country, or provide the same curriculum as the host country? And what impact do both have on the language of delivery, qualification recognition, and finally, the quality of delivery? Greater awareness of the context in which education is delivered strengthens the relationship of teachers and facilitators with the curriculum with which they work. As a consequence, their relationship with the material impacts the manner in which it is delivered and thus the program outcomes.

Hidden Curriculum

It is important to note the value of the ‘hidden curriculum,’ where learners comment on the fact that teachers also model good values and morals. An important question to ask at the crux of this is: what is the definition of peace? Peace could be defined as the absence of violence (negative peace), but can also go much deeper into the absence of structural violence, such as discrimination or gender inequality. In this context, teachers themselves can model perpetration of violence, for example, giving more ”talk time” to boys over girls or in promoting aggressive masculinity and compliant femininity. It is also likely that in these contexts, everyday actions outside the classroom, as well as school policy, will replicate this violence. Consequently, evaluating peace education will be more challenging as the messages delivered in class can differ from general behavior, which is linked to the complex and differing understanding of peace between stakeholders.

Teachers

Teachers are at the core of education. Their classroom practices and discourse determine how and what kind of education and curriculum are delivered. Their effectiveness as teachers impacts what students learn, and which students learn. Long-term, context-based professional development, which values teachers as professionals, will have a positive impact in the classroom as well as on the community. Improved education quality contains the ingredients of peace education. Would it not be more effective to focus on educational quality rather than to bake a different cake that is a lot smaller?

Lucy Atkinson