Tackling urban inequalities requires a plural approach, drawing from community knowledge and experiences. But it can sometimes be a challenge even to harness this resource. Kali Silverman presents the “Ladder of Participation” as a means of shaping a sustainable and practical response to social problems.

In attempting to resolve the growing challenge of urban inequalities, we must actively account for the distribution of resources within three main categories: housing, transportation, and public space. Whereas housing and transportation are heavily bureaucratized systems entrenched in government policy, citizens can wield some influence over their public spaces. Public participation in the public domain can positively influence the development of the environment for, and with, all its inhabitants. As part of the effort to build safer, more inclusive, equitable, and more productive cities, development practitioners must learn how to include local people in the planning process; the question here is how citizens can be co-opted and utilized effectively. Placemaking, the deliberate shaping of the public environment “to facilitate social interaction and improve a community’s quality of life” (Silberberg, 2013, p.2) highlights both the place and the making; the process is the key factor. To understand how communities can become involved in the making and re-making of their own public domain, I reference Sherry R. Arnstein’s “Ladder of Citizen Participation.” This concept frames community engagement within urban public space development initiatives, how the level of involvement affects the project itself, as well as the community’s own development. Once a development initiative has outlined its explicit goals for the public space as well as the community’s engagement, it can then be evaluated for its effectiveness, sustainability, and impact.

Community development is not linear; it is a dynamic and ongoing process, in which various stakeholders, approaches, decisions, and solutions lead to concrete actions. It requires constant attention and effort. The relationship between places and their communities, similarly, is “not linear, but cyclical, and mutually influential.” (Silberberg, 2013, P.11). It is the task of progressive development practitioners to view this relationship as a unique asset in the planning process, rather than fighting against it. Jane Jacobs, urban activist and author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), urges us to examine the essential role of public spaces in cities,

“The spaces between buildings can foster connections of distinct and influential kinds. They shape neighborhood ties. They mitigate against loneliness. They can encourage community action, facilitate political mobilization, help prevent crime and support the socialization of young people.” (Rogers, 2017, p. 23)

Reciprocally, the design of the public realm reflects and shapes values, culture, and social structure, and thus reinforces social hierarchies.

Social injustice is inseparably tied to spatial injustice. As Peter Marcuse urges, “social injustices cannot be addressed without also addressing their spatial aspect.” (2010, p.77) Desired change in the public domain is not just determined by the spatial change itself, but also by the social changes that occur within the space. Public space development projects around the world take on the big goal of creating behavioral changes in the users of public space. These changes cannot alone be expected to result from the spatial changes made in the planned environment; in order to have a real impact, the change must take place from within the community itself. Without community participation, we ignore the social injustice of the space, and newly renovated public space initiatives fall flat. They end up only addressing the visible issues while ignoring the socio-cultural aspects of space, the way residents use the space, and how they maintain the space over time. Through understanding various levels and methods of involving community participation, we begin to think intentionally about how urban design impacts communities and vice versa.

“Without community participation, we ignore the social injustice of the space, and newly renovated public space initiatives fall flat. They end up only addressing the visible issues while ignoring the socio-cultural aspects of space, the way residents use the space, and how they maintain the space over time.”

Sherry Arnstein defines community participation as “a categorical term for citizen power.” Arnstein continues:

“It is the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future. It is the strategy by which the have-nots join in determining how information is shared, goals and policies are set, tax resources are allocated, programs are operated, and benefits like contracts and patronage are parceled out. In short, it is the means by which they can induce significant social reform which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society.” (Arnstein, 1969. p. 216)

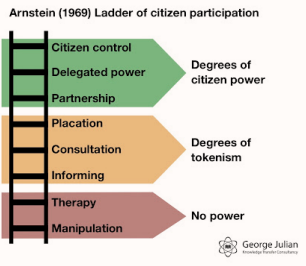

Furthermore, when development practitioners pay attention, there emerges “a critical difference between going through the empty ritual of participation and having the real power needed to affect the outcome of the process.” (there, p. 216) Many government entities and NGOs tasked with development may believe that they work with goals and methods of community participation; but a closer look suggests that the reality of many of these initiatives exists in the “informing” and “consultation” stages of citizen participation, both “degrees of tokenism” as Arnstein explains.

Arnstein’s ladder of community participation is composed of eight rungs divided into three categories, from the least participatory to the most:

“Partnership” enables the community to negotiate with traditional power holders; in this new dynamic, power is redistributed with the help of community consensus-building, creating a relationship in which planning and decision-making responsibilities are shared. Through “Delegated Power” and “Citizen Control,” disenfranchised citizens obtain the majority of decision-making seats, and/or full managerial power. In “Delegation,” the public takes the power and can therefore assure accountability to them. With “Citizen Control,” the community holds full responsibility for planning and managing the project. The general objective for community engagement should be to situate it in the top three “Degrees of Citizen Power,” the green-colored rungs of Arnstein’s ladder: Partnership, Delegated Power, and Citizen Control—even whilst acknowledging that these levels of participation may not always be possible.

Arnstein’s ladder highlights not only intentionality but transparency with the community: a tool to examine and decide on the role that one takes on as a facilitator of development, the role the community plays, as well as each stakeholders’ responsibilities and expectations of participation. No matter the level of community development that existed before the project—no matter the level of disempowerment of the community—it is essential to believe that every community is capable of development as long as we approach the process from their strengths, from their assets. Development practitioners must practice with the belief that this approach can work for all communities, at any level of experience. In fact, community members are the first to see the type of participation they have been invited into, the role they can play in their own development; many development practitioners underestimate the level at which a community can recognize their tokenness or the sham nature of the development.

There is often a disconnect between the ways in which a community is engaged in a development project, and the community’s own development; viewing this engagement as a means to an end, instead of as an end in and of itself. When development prioritizes the community’s process, the community becomes central to the development of the space itself. The process that the community goes through is paramount to the end goals. The community’s own development is—and must be seen as—inseparable from the goals of the project.

An inclusive public space project will only be more relevant, effective, sustainable, and have the greatest impact if it is conceived as an intentional community participation project. I believe that through a clearly stated, intentional community development approach, public space initiatives around the world will be able to create an urban culture of change for the future of neighborhoods and their residents, empowering the community members themselves to take ownership over other aspects of their own lives and futures.

Kali Rifkin Silverman

The Hebrew University’s Urban Clinic’s work with the Bernard van Leer Foundation brought me to their partner organization, Fundación Casa de la Infancia [House of Childhood Foundation] in Bogotá, Colombia. There, I learned first-hand the power of community engagement and ownership, the importance of public space, mobility, and access as it relates to progressive urban planning.