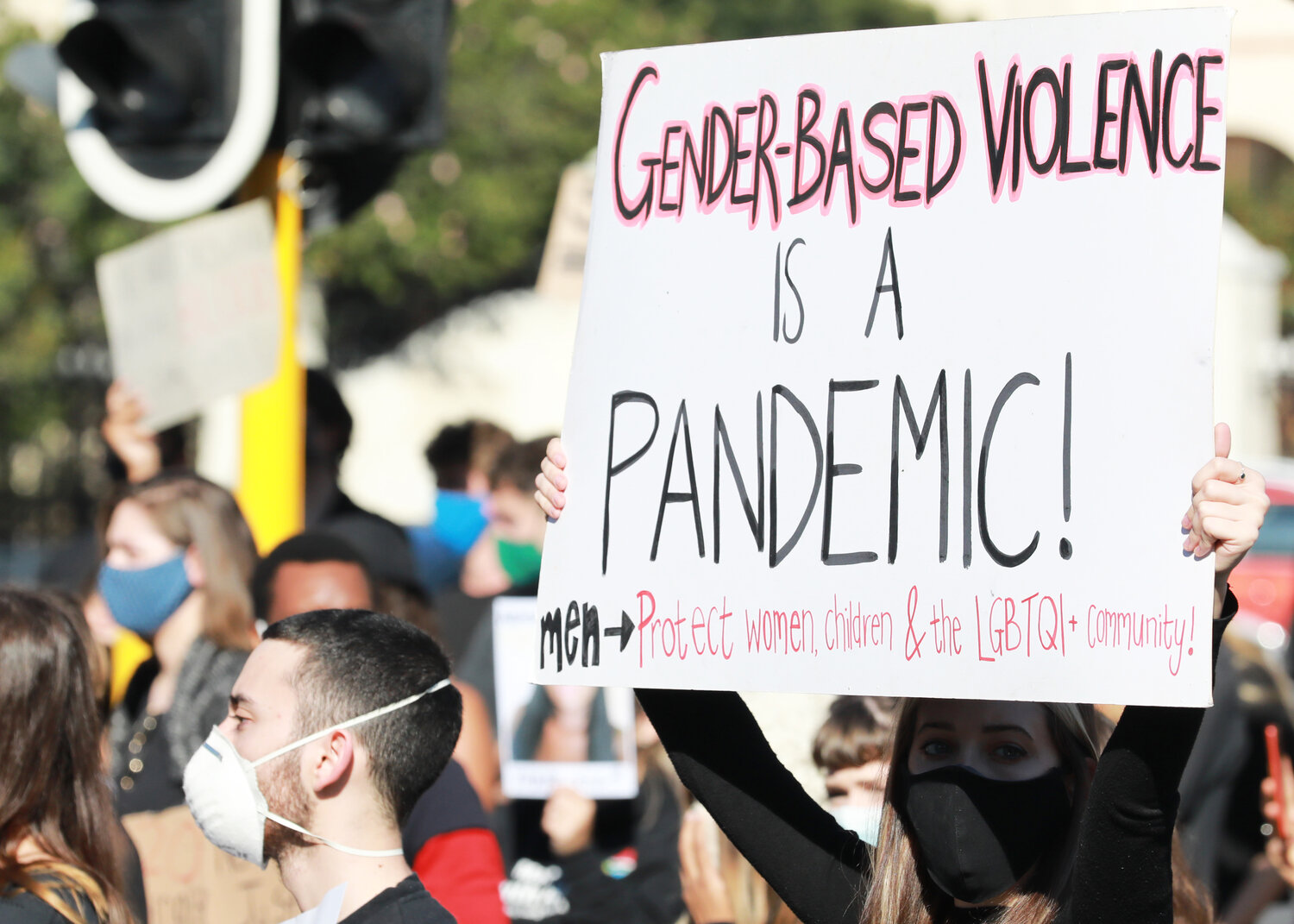

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed society’s ill-preparedness to deal with a persistent scourge: domestic violence. As governments shifted their priorities to addressing the pandemic as a health emergency; funding has been drawn away from initiatives to tackle domestic violence. In parallel, the restrictions imposed by the pandemic have left victims even more vulnerable, leading to a “horrifying global surge in domestic violence directed toward women and girls.” Awareness is the first step toward tackling this problem; a will to act, by confronting difficult questions, must come next.

2020 has presented us with its fair share of new challenges. Most notable is the still ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has affected every country in the world—some worse than others—and has claimed the lives of almost two million people worldwide so far1. In an attempt to defeat this pandemic, “lockdown” has been the go-to policy for many countries. This has presented us with new challenges, completely reshaped and redefined our reality, and has presented us with carry-over effects too severe to ignore, such as economic, behavioral, mental, and psychological problems2.

Domestic violence comes in many shapes and forms, including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. While this problem can affect men, children, and the elderly, it is usually directed primarily against women. Globally, it is estimated that 20-33% of women are victims of domestic violence and that 38% of women murders are committed by a family member or intimate partner3-5. Moreover, The historic link between epidemics and domestic violence has already been established, and the current pandemic is no exception3-5. The worldwide surge in domestic violence forced the Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN), António Guterres, to address the “horrifying global surge in domestic violence directed towards women and girls, linked to lockdowns imposed by governments responding to the COVID-19 pandemic”6, and to call on governments to offer the necessary protection to victims. The UN has coined the term “shadow pandemic” to refer to this phenomenon6. This is also referred to as the “pandemic paradox” or the “quarantine paradox”4,5.

“From oppressive societal norms to complicit policies and weak institutions, the current rise in domestic violence and femicide highlights the state of prolonged neglect that has surrounded the topic for a long time.”

Not to be mistaken as a justification.; it is important to examine how the conditions that cause domestic violence have been amplified and intensified by the pandemic and its related policy changes: loss of livelihood, increased unemployment rates, bans on leisure activities and social gatherings, confining people to closed and sometimes small spaces; combined with living under great uncertainty, and increased agitation and anxiety, these are all factors that cannot be ignored5-7. One of the most cited reasons behind this surge is the lack of “separation”; the time spent apart meant giving the victim a breather and some relief while the abuser was away. Now, the victims have been locked inside with their abusers, living in a constant state of fear. Governments keep telling people to “stay home”; but what if “home” is your own personal hell?

So far, while calls to hotlines have increased by at least 20–30% worldwide, it is estimated that many cases go unreported and undocumented6,8-10. The extent of the problem is even more difficult to assess in countries that lack strong reporting mechanisms. Countries where domestic violence is socially acceptable and hardly criminalized—especially when perpetuated within its rural, marginalized, and minority populations—have also witnessed an increasing number of women who have been killed by a family member, committed suicide as a result of prolonged abuse, or have died of COVID-19 as a result of being denied access to healthcare services (testing, quarantine, and seeking medical help) by their families because it goes against their social norms and traditions8-12.

The pandemic forced most, if not all, national governments to shift their priorities and to direct most of their resources towards fighting it, leaving them over-extended and short on money and personnel. One cannot help but wonder what priority a problem like domestic violence is assigned; whether it is seen as “competing” for needed and relatively scarce resources, mainly healthcare and policing; and whether there is a strong political will, committed enough to fight domestic violence. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) found themselves in a similar unfavorable position as funding fluctuated and donors’ priorities shifted toward fighting the pandemic, forcing them to heavily rely on volunteers. Nonetheless, NGOs advocating for women’s rights took the lead in combating domestic violence, while many governments have been criticized for taking a backseat.

Israel and Palestine are no exceptions. In both territories, similar numbers of women and girls were killed by a family member in 2020 (20 vs. 21)—a statistic believed to echo the increase in deadly street violence. In Israel, a national plan for the prevention and treatment of domestic violence was approved in 2017 but is yet to be implemented. In Palestine, demands for a family protection law are still ongoing.

In the Occupied Palestinian Territories, NGOs were quick to point out that the severity of the situation is the result of entrenched chauvinistic and patriarchal culture, policies, and laws13. Similarly, the situation in Israel was called “a pressure cooker that is about to explode at any time” and a “side effect of COVID-19”14, as complaints have more than doubled since the beginning of the pandemic. Many victims have been denied access to support and protection (due to the lockdown) and reachability to the hotline (due to being trapped with the abuser); so, social media has become one of the most widely used mediums of communication14,15.

From oppressive societal norms to complicit policies and weak institutions, the current rise in domestic violence and femicide highlights the state of prolonged neglect that has surrounded the topic for a long time and the general dependence of state institutions on the non-governmental sector. It could be argued that the pandemic has merely unveiled the ugly truth, showing us how many toxic households exist and how silence can be the most oppressive tool of all. This problem needs to be addressed on many different levels. Oppressive cultural and societal norms need to be tackled; hate speech against women needs to be banned, even in the case of religious speech; and governments need to be urged to establish and enforce preventative and protective regulations. Just like the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence is a public health issue, and it needs to be treated with the same level of commitment.

References:

-

Worldometer, Accessed January 4, 2020: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

-

World Health Organization, 2021. “Violence Against Women” accessed on April 7, 2021: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

-

Bambra, C., Albani, V. and Franklin, P. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Gender Health Paradox.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 1 -10.

-

Singh, T. and Mittal, S. 2020. “Gender-Based Violence During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mini-Review.” Frontiers in Global Women’s Health.

-

Bradbury-Jones, C. and Isham, L. 2020. “The Pandemic Paradox: The Consequences of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence.” Journal of Clinical Nursing (editorial)

-

UN News. 2020. “UN Chief Calls for Domestic Violence “Ceasefire” Amid “Horrifying Global Surge.” Retrieved from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061052

-

BBC News. 2020. “Coronavirus: Domestic Abuse Calls Up 25% Since Lockdown, Charity Says.” Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-52157620

-

Human Rights Watch. “Women Face Rising Risk of Violence During COVID-19.” Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/07/03/women-face-rising-risk-violence-duri...

-

BBC News. 2020. “What India's Lockdown Did to Domestic Abuse Victims.” Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52846304

-

Gil-Ad, H. 2020. “19 Women Murdered This Year: "Corona Turned Homes Into Prisons for Women.” Ynet news. Retrieved from: https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/BycTg8ivD

-

Prince-Gibson, E. 2020. “Huge Rise in Violence Against Women in Israel Met by Poor Response by Government.” Middle East Eye, Retrieved from: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/covid-israel-domestic-violence-women-call-government

-

Oxfam. 2020. “Gender Analysis of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iraq.” Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/rr-gender-analysis-covid-19-iraq-220620-en.pdf

-

Civil Organizations Forum. 2020. “The Murders of Women in the Palestinian Society Take a Serious Turn in the Absence of Laws.” Transcript of a radio interview for Nisa’a FM, September.

-

Sharvit Baruch, P. 2020. “National Security Tools and the Fight Against Domestic Violence.” the Institute for National Security Studies, Tel-Aviv University. Retrieved from: https://www.inss.org.il/publication/domestic-violence/

Amal Khayat

Palestinian from East Jerusalem, she graduated from Glocal in 2016, and from the IMPH (International Master of Public Health) in 2017; the same field in which she's currently enrolled as a Ph.D. student. Amal is also a fellow of the 1325 Women in Conflict Fellowship Programme, a fellow and the Palestinian coordinator of Solutions Not Sides, and an advisory board member of Ladaat - to choose right.